Renewal on the Klamath River

The largest river restoration project ever lifts hopes for renewal on one of Northern California’s great waterways

Under a bridge along Highway 96 in the thickly-forested hills of far Northern California, a small stream enters the Klamath River. The water of Clear Creek is sparkling, crisp, clear and cold. Deep pools in the stream run dark blue and small riffles splash a bright white. Juvenile salmon, steelhead and trout peruse the current, nibbling at drifting detritus. As the clean water reaches the confluence, it’s gobbled up by the warm syrupy gray current of the greater Klamath River.

The difference in water quality between the stream and the river is stark, and it tells a story. The Klamath River is not healthy. The 257-mile river, once the second largest by discharge in California, is too warm and too contaminated to support a robust salmon population. For nearly 100 years, flows have been reduced and many of the cold, clear tributaries—critical spawning habitat—have been blocked, pouring into the sun- baked algae-filled reservoirs created by upstream dams. But the waterway and the dams that have maimed its original breadth are on the precipice of monumental change.

The Klamath River Dam Removal Project

Starting in 2023, one of the Klamath River’s dams has already been removed and three more will be deconstructed in 2024 and the riparian habitat in the resulting canyon will be recreated—a project that’s been talked about for two decades. After the project is complete, the river’s water will run clearer and colder. Salmon will have access to more than 400 stream-miles of original spawning territory, including dozens of tributaries that were cut off by the dams. The project will constitute the largest river restoration in history. Many hope the end result will be a vitally different river, one that hosts a strong salmon population and supports Native Tribes’ traditions, as well as a strong economy based on sustainable recreation.

“It’s unreal to actually see the things that so many people in my life fought for come to fruition,” says 20-year-old Danielle Frank, a Yurok and Hupa tribal member, who’s spent most of her life fighting for the dam removal. “I’m really excited knowing that it’s actually real, that it’s actually happening right now.”

When will the Klamath River dam removal be complete?

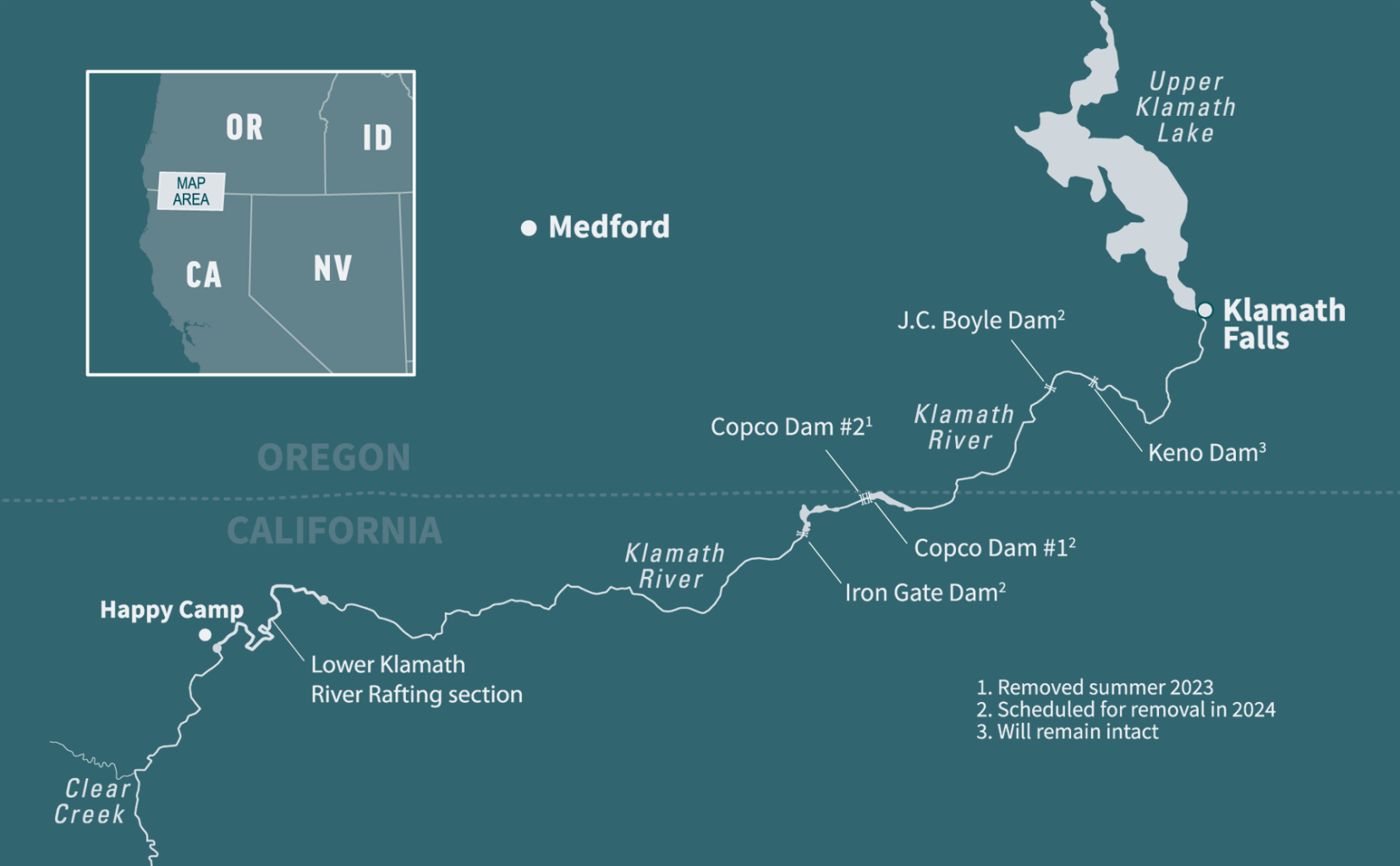

The Klamath River originates in Oregon’s Cascade Range with spring water and runoff flowing into Upper Klamath Lake. Past Klamath Falls, the river meanders southwest through a series of canyons and reservoirs. Removing the J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2 and Iron Gate dams will create a free-flowing river below the Keno Dam.

The first and smallest of the four dams, Copco No. 2, was removed during the summer of 2023. In early 2024, the reservoirs behind the remaining dams will begin to be drawn down. The three remaining dams will be removed throughout 2024, with demolition scheduled to be complete by the end of that year.

As the water drops in the reservoirs, restoration crews will start planting seeds in the freshly exposed and still moist sediment.

“Around March and April [2024], we will have crews out there walking around on the mud with something akin to snowshoes so they don’t sink hip deep,” says Dave Meurer, a spokesman for Resource Environmental Solutions (RES), the company that’s been contracted to manage the replanting of the reservoir footprint. “To take advantage of the moisture in the sediment, we want to broadcast seeds and kind of chase the water level down.”

To complete the revegetation, RES has worked with commercial nurseries to propagate 17 billion seeds from 98 different native plant species. The new plants were created from seedstock that was collected by hand by Indigenous Peoples in the Lower Klamath River area. Even with 40-50 people working, revegetation and environmental restoration may take up to two additional years.

What will the river look and feel like once the dams are down?

As the water drops in the manmade lakes behind the dams a huge amount of sediment will be left behind. Crews will spray the fine silt with fire hoses to try to move the mud into the water column to hopefully get it to flow down- stream.

“It will have a peak turbidity and be really dense early on, and then it will taper off,” says Meurer. “It may take around two years to get the water quality and clarity to where we want it, so we’re not seeing the effects of the removal.”

Once the canyons are replanted and the sediment has stabilized, the river will hopefully be more reflective of what was there prior to the dam projects. With a dam at Upper Klamath Lake and a dam in the small town of Keno, Oregon, the river is not entirely free flowing. Flows of the river will still be controlled by the Bureau of Reclamation. But many of the previously cut-off tributaries will contribute clear and cold water to the Klamath, hopefully creating a healthier ecosystem.

“Because we have all this accumulated sediment, it’s going to take us a little bit of time to really understand how these fluvial processes are going to take place,” says Mark Bransom, CEO of Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the organization that’s managing the project. “Ultimately, we have a pretty strong sense that the river will reoccupy its historic channel and there are some features that we expect to be restored over time like Moonshine Falls in the JC Boyle area.”

Though the flows are anticipated to be similar to the flows that existed before the dams were removed, there may be some seasonal fluctuation due to the many restored tributaries pouring directly into the main stem instead of reservoirs. This is also expected to affect the temperature of the water. Without the reservoirs, basically large heat sinks, the river should run colder—a boon to salmonids and other native aquatic species.

With the dams gone, more sediment and gravel should move through the river channel, scouring and scrubbing the bottom, which helps remove algae from the rocks, resulting in a river that looks and feels more like the beautiful blue water of Clear Creek.

“A lot of our people say that the river knows how to take care of itself,” says Frank, who’s studying hydrology at College of the Redwoods and plans to move to Cal Poly Humboldt in 2024. “It will be great to see that process take place.”

What will a restored river and watershed mean for salmon, steelhead and the native peoples who celebrate and rely on the fish?

Dam removal on the Klamath first received public attention and broad consideration after the fish kill in 2002. That year, intensely warm water and low flows allowed a bacterial infection to invade the already struggling salmon popula- tion, killing tens of thousands of individuals and fueling a public outcry.

“Our people say it was more than 100,000 washed up,” says Frank, who was born the same year. “Everywhere you could see were dead salmon. My dad described to me walking out of the house and just smelling death.”

The salmon populations in the Klamath River were once the third largest on the Pacific Coast, according to NOAA Fisheries. Tribes along the Klamath, including the Yurok, Karuk, Klamath, Hupa and Shasta, have relied on the Chinook, Coho and Steelhead for traditions and sustenance for thousands of years.

The dam removal is expected to broadly increase the salmon population and have other broad benefits to the aquatic ecosystem. Though an exact number of returning adult fish isn’t clear, the return of the fish—and in turn the commercial and sport fishermen and fisherwomen—will be very much looked at as a measure of the project’s success, says Bransom.

“More broadly, there is a hope that the dam removal and the environmental restoration will promote social and cultural rebalancing,” Bransom says. “And I say that in particular with regard to Tribes whose livelihoods and social and cultural ways of life were disrupted as a result of the significant reduction in salmon.”

What will the dam removal mean for rafting and paddling the Klamath?

For paddlers, the project will allow trips to connect the section above the dams with the rest of the Lower Klamath River and even float all the way from Keno Dam to the rivermouth (with at least one portage)—a float of over 200 miles.

“It could become one of the best multi-day rafting trips in the country,” says Michael Wier, an avid fly fisherman and rafter, who works for California Trout, one of the 41 organizations that originally signed the Klamath Agreements in 2010.

It’s unclear at this time if the dam removal area will be a viable stretch for commercial outfitters, but there’s a lot of hope for many fun new options for paddlers. Several new river access points are built into the restoration plan for the hydroelectric reach.

The non-profit Rios to Rivers is working with a group of Indigenous youth to do the first source-to-sea kayak descent of the Klamath once the dams are down. Frank is a board member for the organization and has been learning to kayak alongside the youth. Rios to Rivers is involving the youth in the project in a number of ways, including taking them to see the dams coming down and helping in the revegetation process.

Frank hopes getting involved with the dam removal will leave an impression on the young people. She remembers her first protests well and how her father and uncle pushed her to use her voice. For her, the dam removal is a win that means a lot.

“It’s very personally meaningful because a lot of the people who taught me to care about these things are no longer here,” she says. “My dad and my uncle and a lot of the people who I grew up watching fight for this have passed away. Seeing their dreams come to life is pretty special.”

The 2024 Klamath River Rafting Outlook

Due to ongoing construction and anticipated (as well as unknown) impacts from the Klamath River dam removal project, OARS does not expect to operate any trips on the Lower Klamath in 2024. However, we’re excited for a dramatic recovery in the coming years and are now taking advance reservations for 3-day trips on the Lower Klamath River between Sluice Box and Happy Camp for the 2025 rafting season.

Related Posts

Sign up for Our Newsletter