True Tales from the First Descent of Chile’s Legendary Bio-Bio River

40 years after their first descent of Chile’s Bío-Bío River, Richard Bangs reflects on OARS Founder George Wendt’s gamble and the legacy that would follow…

To the uninitiated, George Wendt seemed breathtakingly ordinary. He was anything but.

Of quiet disposition, wearing the cloak of an academic, George beneath was an action hero, and his quest to make the first descent of the Bío-Bío tore off his mask, at least for me.

George had been my partner for a couple of years, and we worked shoulder-to-shoulder in his dank, crowded basement writing brochures and making phone calls, trying to convince an unversed public that international river running had merit. Then one day George’s cousin, Bill Wendt, chief ranger at Yosemite National Park, walked in carrying a map and an idea. On a United Nations exchange program, Bill had spent three years surveying the park potential of Chile, and had flown over and hiked a portion of a river corridor he thought was exceptional: The Rio Bío-Bío. Bill was not a river runner, and thus was unqualified to make this assessment. As we looked at the map of Chile it showed that this thin ribbon of a country was just 113 miles across at its widest. The odds of finding a navigable whitewater river of any length seemed poor.

Yet, at that moment, George, at his best malgré lui, displayed several of the qualities that would help usher the global crusade of river exploration. He said, “Let’s give it a try,” showing a willingness to make a gamble for the sake of a shared passion, and for trust in somebody with a wild idea, but little experience. He was willing to commit time, money, effort, and risk into an expedition that probably every other experienced outfitter of the day would have dismissed as crazy. I gave George the Sobek handshake, devised on the Omo River in Africa…palms raised as the open mouth of a crocodile, and snapped shut around the hands of a kindred spirit.

It turned out the Bío-Bío was every bit as epic as we might have hoped, and it quickly became the world standard, and the most popular run in the Sobek repertoire. For years guides and river enthusiasts alike traveled to Chile to experience the magic and power of the Bío-Bío. When Endesa, the Chilean power company, decided to build a dam that would flood the heart of the Bío-Bío, George and hundreds of others who fell in love with the river (including Al Gore, Robert Kennedy, Jr., Sting, and Barbara Boxer), fought to save this extraordinary passage. But, insanity prevailed, and now the song of the Bío-Bío, which George helped to popularize, has been silenced. But, the memory of George’s gamble sings on.

Read the full account of the first descent of the Bío-Bío from the book Rivergods, Exploring the World’s Great Wild Rivers by Richard Bangs and Christian Kallen. Reprinted with permission below.

River of Song

It was a long shot. We knew practically nothing of the river, only that it was Chile’s second longest. Yet in a country measuring 2,600 miles long and just 113 miles across at its widest, the odds of finding a navigable whitewater river of any length seemed poor. We had no hydrological data, no flowcharts, not even good maps. For all we knew, the eddies south of the equator spun counterclockwise. But Chile did have a promising source of whitewater: the Cordillera de los Andes, the world’s longest mountain range and one of the highest. And the name of our target river, the Río Bío-Bío, had a fanciful lilt that put a smile on everyone’s lips. After struggling with names like the Çoruh, Tuolumne and Tatshenshini, this river sounded like a song.

And that is just what it is: the Mapuche Indian word for the song of a local flycatcher, the Chilean elaenia. The Bío-Bío (pronounced bee-oh bee-oh) springs from Lago Galletue, a shimmering alpine lake at the foot of 10,000-foot peaks a few miles from the Argentine border. The river flows from near a town called Sierra Nevada in a grand arc, skewing south, then dodging off to the west, passing through the village of Santa Bárbara and the town of Los Angeles (near San Fernando) before finally spilling into the Pacific. It all sounds hauntingly familiar to a Californian.

The Bío-Bío had been called to our attention by Bill Wendt, chief ranger at Yosemite National Park. He had spent three years in the area on a United Nations project and had flown over and hiked a portion of the river. Although he knew little of river running and had seen only a fraction of the Bío-Bío, he spoke glowingly of its clear gushing waters and the landscape through which it flowed.

While making plans to run unrun rivers was no longer new to us, committing the time, money, and energy on the basis of so little information made us uneasy. Nonetheless, Bill’s confidence and excitement were contagious; and six of us were gamblers enough to throw our hats into the ring, including Bill and his cousin George Wendt, owner of a California river-rafting company and a Sobek partner from the beginning; Mike Cobbold, a seasonal Yosemite ranger who also worked for the Park Service in Chile; and three Sobek river guides; Brice Gaguine, Jack Morison, and Rich Bangs.

In December 1978 we flew from San Francisco over the equator, reaching Chile at 17 degrees south, well within the tropic zone. The country we saw below us was barren, sparsely inhabited desert spreading across the western flank of the Andes. By the time we landed in Santiago, Chile’s largest city, we had reached the more comfortable temperate zone, and the plain between the Andean peaks and the Pacific tides was full of angular fields devoted to grain and grazing. Santiago is only half-way to Chile’s southern reaches, the land’s end of South America.

In Santiago we transferred all our gear to the train station: two fat rolls of neoprene that would inflate to Avon Professional rafts sixteen feet long, nine ten-foot-long ash oars, a dozen metal ammo boxes (which never fail to raise a few eyebrows at the customs lines) to keep our gear dry, a couple of eighty-quart coolers, and the six-foot-long aluminum alloy pipes that fit together to form rowing frames. We enlisted a few eager teenagers at the train station to help us load it aboard and took the modern diesel train south to Victoria, a small farming village in the Andean foothills. There everything was unloaded onto the old wooden station platform, and we sat down on the pile of equipment to wait for the arrival of the steam-powered, narrow-gauge engine that would take us up the old spur railroad into the Andes. Finally it arrived, smoking down the tracks like the long-awaited rendezvous with destiny in High Noon. We hefted all our gear into a baggage car and took our seats on the antique red leather bench seats. Then the steam engine belched a cloud of dark smog, sending sparks scattered over the tracks, and lurched and staggered its way out to the station, plunging almost at once into the Andes.

The Andes are one of the most impressive geologic formations on the planet, a single mountain range, predominately volcanic, over 4,000 miles long, created along the entire west coast of South America, from Colombia to Patagonia. While its highest mountain, Aconcagua (just to the northeast of Santiago, in neighboring Argentina), measures 22,831 feet, which barely joins the top twenty summits, the average altitude of Andean peaks makes it the world’s highest range, behind the Himalayas. A range that long and that high has just about every mountain phenomenon: remote and rugged summits that defeat the best mountaineers, sharp glaciated ridges that forbid overland travel, and popular ski resorts surrounding pristine alpine lakes.

The railroad into the mountains followed the line of least resistance and, avoiding the peaks and ridges, took us to Temuco, a small town in the heart of Chile’s wine-growing region. Today Temuco is the northern limit of the Araucanians, a native people who have been singularly successful at avoiding conquest. The people derive their popular name form the araucaria, or Chile pine, known also as the monkey-puzzle tree because its long spidery branches are covered with stiff green needles that remind some people of monkey tails. The Araucanians call themselves Mapuche, however, which means “people of the land.” They are for the most part sedentary, agricultural people who in centuries past hunted guanacos, pumas, and armadillos—and, when their security was threatened, invaders.

In the years of the expansion of the Incan empire, under Tupa Inca’s leadership during the years 1463 to 1493, the Incas were stopped in their conquests at the Maule River, some fifty miles north of the Bío-Bío. There fierce Mapuches armed with bows and arrows showed the Incas that were, at last, too far from their homeland. In the century that followed, the Mapuches resisted conquest by Spanish forces under Pedro de Valdivia, who solidified the conquest of Chile. Valdivia was slain in battle against the Mapuches in 1553. For 300 years after that, the Mapuches continued to resist conquest and assimilation; until 1882, in fact, the region of Chilean national authority ended at the Bío-Bío, despite the maps that showed but one country. Below that river the Mapuches continued to live apart.

While no Incan, Spaniard, or Chilean has ever conquered the Mapuches, the slow but inevitable effects of contact and commerce have brought them closer to the modern age. Now they raise wheat and barley as well as the traditional maize and potatoes, and breed cattle and sheep, like much of Chile’s rural population; but the Mapuches continue to be one of the largest functioning indigenous societies in South America.

In Temuco we picked up a seventh expedition member—Alejandro Sepulveda, an administrator in the Chilean Park Service and an old friend of Bill Wendt’s during his Chilean sojourn. Alejandro had set up a flight over the Bío-Bío so we could evaluate our destined course before it was too late. We flew from Temuco over the river, soaring over nearly 200 of the river’s 240 miles, from Santa Bárbara up to its source at Lago Galletue, searching for obstacles that might end our expedition before it got on the water. The river did look runnable, with one series of four big rapids that promised excitement, but no major waterfalls or other impassable obstacles. None that we could see, at least, for the river at one point played hide-and-seek in the narrow canyons of the Andes. We congratulated Bill on his choice.

That evening we finally reached the river’s source after a half-day’s ride in the rear of a cattle truck over Chile’s back roads. Some Lago Galletue residents killed a lamb, cut its throat, collected the hot blood in a wooden bowl, and dropped in a lemon wedge, which coagulated the blood into chinks that looked like four-day-old cafeteria Jell-O. It is called nachi, a delicacy reserved for special occasions. We were honored, and rushed to wash it down with pisco, the clear brandy of the Andes.

We spent much of the next morning rigging up for our expedition. The rafts were rolled out and, with the help of a high-volume pump, assumed their familiar shape. Four separate chambers create the oblong perimeter of the rafts, with two thwarts placed in the center to add stability. Each chamber is inflated to drum-hard tightness, so the raft rides high and firm in the water; the chambers are separated by baffles so that, in the unlikely event one should pop because of a sharp rock, crocodile teeth, or overinflation, the other three will keep the boat afloat. During the twenty-five years of professional river rafting, the standard configuration of the raft—its dimensions, including the tube diameter, uplift at bow and stern, and placement of D-rings for tying on gear—has been refined to a very specialized level. Today’s riverboat is a far cry from the surplus landing craft that first found its way downriver in the years following World War II.

Next, the two-inch-diameter aluminum tubing was assembled into the rowing frames. They are equipped with the essential oarlocks and also supply stability and rigidity to the raft. When lashed securely into the midsection of the craft, the frame allows gear to be tied onto a wood panel floor section that is dropped between the thwarts. Coolers, ammo boxes, stove, fuel, water jugs, heavy cast-iron Dutch oven, and other paraphernalia are then all secured to the deck, while the water-tight black bags containing dry clothes are tied into the rear bilge section. The weight of the gear, riding low in the boat, adds further stability to the raft in the torquing and twisting of powerful hydraulics. Everything is lashed down securely, either to the boat or frame or both, to prevent its loss in case of a flip.

Finally all was ready: the oarsman was braced with his feet between the gear on the floorboard, with a spare oar tied by slip-knot within easy reach; passengers took their places in the front section for weight balance against the black bags in the rear—and for a thrilling, wet, front-row seat. All the tied-in gear was checked and double-checked; lifejackets were pulled snug. Upstream, the snowy crown of the Volcán Llaima, scraping the skies above the Lago Galletue; downstream, the river.

As a condor caught an air current overhead, we shoved the rafts into the water, spun into the current, and whirled downstream. The first rapids were shallow, rocky, and couched in a small canyon topped with thick araucaria trees, which cast a magical aura over the river. Twisting through this watery maze, I was struck with the ghostly feeling of unfamiliarity. The river seemed like none other I had experienced. The River Styx, I felt, might bear some resemblance.

The water was crisp, clear as pisco. It almost crackled with each stroke. We pumped and shot through channels and chutes and drank in the scenery. The area we were traversing was called the Switzerland of South America. That does it an injustice. The backdrop was the unique snow-capped Andes, an endless phalanx of three-dimensional points that blends with sky and clouds without clear definition. Closer stood the perfect, snow-dripped cone of Volcán Llaima, poking 10,000 feet into the clouds. (RB)

In those first twenty-five miles the river left the alpine Andean forest of araucaria and flowed across a broad foothill plateau; above the gentle banks, green fields sloped gradually to the bases of the surrounding mountains. Our aerial survey had given us the foreknowledge that later when the river poured off the escarpment, we would plunge through dark gorges in a fierce region—a junkyard of the spare parts of mountain building. But for now the landscape was smooth and sweet, and we savored its comfort.

Horsemen decked out in silver spurs and leather rode to the edge of the river and gaped at the gringos locos. Horses, pigs, and sheep wandered along the cobbled banks, and at one small farm along the river a local cowgirl tried to sell us a live goat for dinner. It was like being in the real Wild West, from the steam engine burrowing into the mountains to the broad-chapped cowboys waving their laconic greetings. And, from what we’d seen of the river from the air, the broncobusting was yet to come.

Our first night’s camp was on a broad green velour-textured embankment with a downstream vista of saw-toothed, snow-draped peaks. The night was our real introduction to the Southern Hemisphere: our latitude was about 36 degrees south—the southern equivalent of Carmel, California. We savored a dinner of fresh vegetables and fruit, bantering in shirtsleeve warmth and familiarity beneath a crisp sky speckled with unfamiliar stars.

As we lost elevation, the flora and geology began to change. The towering araucaria pines—which can grow to 150 feet high—gave way to groves of cedars, Lombardy poplars, and cyprus festooned with long shags of Spanish moss. The river began falling into a burnished gorge. Evidence of human habitation began to disappear, and the roots of the Andes were revealed in layers of basalt, pumice, and andesite—the igneous substratum of the great range. There was a sense of leaving behind the commonplace, of gliding toward the unknown.

As we passed the creek mouth, we saw a lone fisherman working a line with a crude sapling pole. This prompted Bill Wendt to try his luck, and he cast his nylon line over the stern. Seconds later he brought a five-pound brown trout flopping into the bilge. He whooped and hollered and threw the line in again. Within seconds he had another strike, and another five-pounder.

All this served to fuel the predator instinct in Bruce Gaguine, and when we passed a giant European hare (the size of a cocker spaniel) loping through the bush like a target waiting to be hit, Bruce got an idea. He had us pull to shore, where he filled the bilge with golf-ball-size rocks; then we pushed out into the river again, creeping stealthily downstream looking for prey. We saw no more hare, but geese were everywhere. With every turn Bruce sprang into action, spitting rocks from his hands like gunfire.

Preoccupied with the hunt, he didn’t notice when the boat was sucked into a rapid littered with boulders and chopped with three-foot drops. While novice river runner Mike Cobbold was at the oars, Bruce was crouched in the bow, still clutching ammunition. Suddenly Mike lost control: the boat rode up on a rock, waffled, and turned on its side, and the river started flushing in. Bruce leapt to the oars and wrestled the raft off the rock and through the rest of the rapid. Since we were the first to negotiate this river, we had the prerogative and privilege of naming rapids. This one became Gaguine’s Gauntlet.

We purled past Chilpaca, a ghost town that thrived during a gold strike in 1932. Then we left the inhabited regions behind and were drawn into a forested whirlpool as the sun dropped behind a distant volcano. Camp was at the foot of a tremendous, frothing, white cascade of a tributary.

The next morning was Saturday, and we decided to treat it as such. Scanning our maps, we found a lake just two miles up the tributary, Lago Jesús María. We decided to investigate and scrambled up the rocky stream. Before long we reached it, and it was beautiful. The deep-blue, sun-dappled glacial basin was encased by 6,000-foot-high granite points, spires, and flutes, with tears of snow running down steep valleys on its flanks. It looked very much like one of the Twin Lakes in Yosemite, except for the absence of campers. We reveled and sunned in the wildflower meadows; but the promise of rapids downstream on the Bío-Bío called and we returned to its banks before noon.

Running downstream once again, we splashed and careened through scores of rapids, naming them all as we went. With every passing mile the river was showing us a combination of the best features a river can have: resplendent scenery, powerful rapids, clear water, and good fishing.

That evening we feasted and feasted. Bruce got lucky, so local goose was roasted while the hunter-chef prepared a liver pâté. We mixed pisco sours for cocktails and spread coals from our campfire beneath and on the lid of the Dutch oven. While heat surrounded the pot and radiated through the cast iron, we awaited the exotic concoction for dessert. Finally dinner was ready: we uncorked a bottle of Chilean wine (70¢ for the wine, $1.70 for the returnable bottle) and ate corn on the cob, chicken soup, barbecued goose, and, finally, fresh cherry-vanilla pudding—the product of our Dutch oven.

On Sunday, distended bellies notwithstanding, we rolled onto the river at 11:00 a.m. At noon we pulled over to a cascading tributary with a promising name, Río Loco, and noticed some strangely discolored rock: mineral hot springs. “Doesn’t this river ever stop?” Jack asked in wonder as we lay back for a soothing soak. “What more can it give us?” If the Bío-Bío heard that question, the river took it not just as a compliment, but as a challenge. Downstream we hit the first of the big rapids.

We were suddenly in water as violent and complex as any we had met, and it sent pulses thumping and spirits soaring. One rapid had a hole a small hotel could get lost in, in river dead center. Another had a glassy chute that slid over a twelve-foot drop and ended in a back-rolling column of water, a horizontal tornado. Another was a 500-yard labyrinth, through a team of basalt rock bone-crunchers positioned like a defensive line.

In the middle of the rock maze, a glacial stream, gray with silt, spit into the river. As we scrambled up the bank to scout, we could see the source of the stream—a fantastic glint of ice, pouring down through a mammoth mountain cleft like a huge strand of frozen molasses. It was an unnamed glacier, a stream of brilliant blue light carving through a realm of black basalt and ash. Ignoring for the moment our scout, we climbed higher, and the view got better. The glacier hung from the 10,000-foot cone of an active volcano, Volcán Callaqui, a belching, smoking, snow-creamed peak that loomed directly over the river. We paused in amazement and excitedly pointed a route up the broad snowy flanks of the volcano. Perhaps another day; this one was for running the rapids.

Reluctantly we turned our attention to the rapid and descended to walk along its banks. We shook our heads in dismay, then paused in concentration, and finally nodded with understanding. It was, perhaps, possible, and a portage would not be easy. It took half an hour to memorize the run, which zigzagged through the rocks in a broken course. At last we walked quietly back to the boats, checked the rigging, and pulled tight our lifejackets. The oarsman slipped on his soft leather gloves.

I began the run, drawing on the oars methodically, trying to match the map in my mind with the frothy view crashing down my bow. The current was fast, and from the river the perspective was disorienting. Almost at once I lost my way. I fell back on my instincts and had to rely on snap judgments and quick action. As I pulled to miss an approaching rock, I suddenly realized I would not make it. Whack! The collision felt like a VW bug in a head-on with a Mack truck. The boat buckled, rebounded, fibrillated, then snapped around the wrong side of the rock, straight toward a deep-throated hole. Miraculously we were all still in the boat, and we braced for the hole.

We were flushed out immediately and couldn’t believe it. But once we were out of the rapid and around the river, before our blood vessels got a chance to relax, the view downstream sent our hearts into our throats. Just 200 yards away was one of the most incredible river sights I have ever witnessed. A 150-foot tributary waterfall leaped in a show of shimmering, reflected light off a sheer cliff of columnar basalt and described a gentle arc as it crashed directly into the river. Most rivers of appreciable length offer tributary waterfalls that can knock the breath out of any mortal; but such falls are usually a long way off the mother river, sometimes a hike of many miles. Never had I seen such a dazzling display of water and light spuming and mixing into a main river. It would have been a crime to continue, so we pulled in directly across from the waterfall to make camp. (RB)

After a hypnotic dinner, with the eyes of seven chewing heads trained on a common spot across the river, a small group managed to break loose to hike downriver. It was a mistake. The next rapid was the biggest yet, a fuming, frothing, mad jitterbug of big water dancing and tripping through king-sized holes and against Statue of Liberty boulders. We continued downstream to see if there was a calm stretch into which we could pull flipped boats, should we attempt the rapid. There wasn’t. After 500 yards of fast, eddy-less water, the river pinched against the south wall and created a quarter-mile-long toboggan run that dumped through half-dozen major souse holes and twice as many pressure waves. Finally, far below, a long, sleepy stretch of water waited, where the pieces could be picked up.

We couldn’t remember spotting these rapids from the air, and we had seen some bad ones. But a worse rapid than this seemed unimaginable. To climb out of the canyon would be less than easy, and to portage half a mile over slippery, uneven terrain would be just a hair more fun than rolling boulders uphill all day. No one slept well that night. Only the spectacle of a shaft of moonlight playing on the milky waterfall across the river distracted us from our worries for a while.

No one was hungry the next morning, so we skipped breakfast and marched down, a funereal procession, to the first rapid. Jack Morison, a ten-year Colorado veteran, commented with a grating crack in his voice that this was the first rapid he had seen that was more difficult than Lava Falls on the Colorado—a rapid considered by many to be the toughest piece of whitewater in the U.S. After eyeing the stretch in the warming light of morning’s optimism, we decided it was possible to make the run down what we were now calling Lava South. Besides, it would be far preferable to run it than to portage, though the consequences of a mistake could be dear.

Alejandro looked at it and told us he could round up horses to get us out of the canyon. When we didn’t respond to his offers, he told us he had two kids, cute with brown eyes, and elected to walk the rapid.

Bruce rowed first, as Bill and I rode the bow. We pivoted past the tributary waterfall, a grand, miraculous sight, but we couldn’t dwell on it. Survival superceded our sense of aesthetics, and all attention was directed downstream.

Brice made a good entry, but smacked into a lateral wave that turned him the wrong way. The path devised while scouting from shore was the path not taken. We suddenly washed broadside against a boulder bar bisecting the river, and the boat started to ride up on its side, the first stage of a flip. Bill and I threw our weight on the rising tube, and the boat slid off the rock, around the far side into a channel we hadn’t been able to see from shore. We were out of control in unknown water. We careened toward a pair of basalt slabs, smashed into one, spun on our side, and flopped down to the rapid’s end, right side up. The bilge was brimming with water, and as Bill and I frantically bailed, Bruce pulled to shore on a broken oar. But we made it! (RB)

The day continued with a seemingly endless cascade of rapids. At one, Alejandro met a Mapuche Indian who described a recent drowning; and, as it turned out, the victim had been a friend of Alejandro’s. At the next rapid, Alejandro explained he had three children, just school age, and again he volunteered to walk.

At another sharp rapid, Jack and George were kicked out of the boat. As Jack was thrown out, his tennis shoe caught on the oarlock, and he ended up dangling helplessly upside-down in the water, dragged along like a stunt man behind a horse. But this was no stunt: he struggled to keep his chin above the water and to wrench his shoe free while the boat drifted toward the next cataract, a bad one.

The scene seemed too melodramatic to be real, but a watery scream from Jack dispelled the theatrical illusion. George Wendt splashed back into the bilge, grabbed the oars, and wrested the raft back to shore, while Mike plunged out of the boat next to Jack to help pull the caught leg free. Coughing and sputtering, Jack dragged himself up the beach, a vacant, hurt look in his eyes. He’d come close: it was a freakish close call. Some nasty bruises and a deep cut testified the river couldn’t be messed with.

Later that same day Bruce, too, paid his dues. After several cautious, successful runs, Bruce decided to run left though a rapid Jack had already run down right. It was a mistake.

We suddenly plummeted though space toward a rock at the bottom of a fifteen-foot hole. We smacked, buckled, twisted, and almost flipped, and Bruce hurtled overboard. I sprang to the oars just as the raft slammed into a cliff. We bounced off, and a few hard pivot strokes spun us into an eddy. No sign of Bruce. A few seconds passed, those steel-cold seconds in which everyone wonders if the worst has happened, then we all broke into a chorus of screams. I felt the floor of the boat bump twice and realized Bruce was stuck underneath. I jumped on to the side, about to dive in, when a blue-faced Bruce popped up, alive and sputtering next to the boat. (RB)

The day had been too intense to continue any further. We’d run more big rapids in a single day than are run in twelve days on the Colorado. and a couple were as big as the biggest in the Grand Canyon. We camped across from another 100-foot tributary waterfall, one of dozens that grace this canyon, but we were too weary and jaded to give it proper attention. It was like trying to admire a beautiful painting after having been mugged. We slept in exhaustion, unable to worry about what tomorrow might bring.

The next morning, our sixth on the river, was crisp and clear as a bell. Alejandro went for a hike during breakfast and came back with information some Mapuche Indians has passed on to him. They said there were twenty-three miles of bad rapids ahead, worse than what we’d been through including a major waterfall. He’s also heard a rumor that another group had tried to raft the river five years earlier, but they had lined their boats for days down to the first big rapid (which we had hit two days earlier) and there they walked out. Prudent, sane men. He concluded by relating the popular local legend of chenque, a cave deep at the bottom of the river where those who drown go. There they live forever, a very good and happy, though perhaps soggy, existence, but they can never resurface.

As was by now the pattern, the morning unrolled a stream of thrilling rapids. At noon, after a surprisingly nasty rapid that we navigated without mishap, we reached a red light. The river pinched into a sliver, barely fifty feet wide, and zigzagged through two tortuous right-angle turns. Most of the water jetted around the first corner, slid down an eight-foot sluice, and crashed into an overhanging cliff on the right. Overhangs—wedges of rock just above the surface—are major risks. Each year they drown a few hapless kayakers and occasionally some rafters. If a boat or body gets swept into an overhang, it easily can get pinned by hundreds of pounds of water pressure, making it impossible to escape.

The overhang ahead of us, coupled with the fact that the next three rapids, all in close succession, were horrendous, gave us pause. We were certain we had now reached the series of difficult rapids we had spotted from the air. From high above, they had all looked runnable. Ground level had a different story to tell. After an hour of scouting through virtually impenetrable brush and after much deliberation, we decided to portage one boat and position it in the water downstream from the falls. There, we hoped it could catch the other boat, should it capsize.

Alejandro had taken little time to decide to walk out to the road and hitch to Santa Bárbara, our take-out point. He felt sure his four hungry children would want to see him again. So Jack Morison, who had not upset a boat in ten years of river running, started into the rapid with only one crew member. All the others, save Alejandro, were stationed in the other boat below, with coiled safety lines in readied hands.

“Whatever you do, Rich, stay away from that wall,” Jack had warned as we pushed off, as if I might skip out of the boat and splash over to the wall for a playful inspection. Still, the tension in his voice put a lump in my throat.

His setup was perfect. He made it all the way to the top left, where the water was safest; but too quickly the current changed and pushed the raft into the right sluice that rammed into the overhang. The wall bore down on us at an alarming speed; I could see the dark recesses of the overhang getting bigger, enveloping the total picture of possibilities. I jumped back, and bam! We hit the wall at a forty-five-degree angle, and the boat ever so slowly slid up the wall, wedged briefly in the overhang, then tipped over. I jumped clear, as did Jack, and we were flushed safely to the eddy below. His first flip—after ten virtuous years of rafting.

Instinctively Jack and I grabbed the D-rings of the boat and tried to drag it to the right shore. It was as cumbersome as a pregnant hippo, and I found myself quickly exhausted. We made one small eddy, but couldn’t find a handhold or break in the rock to climb out, so we slid back into the current and down around the corner toward the next rapid. The other boat showed in the nick of time and pulled us in barely twenty-five feet above the angry water. Had we been sucked in, we probably would have lost the boat and gear forever, to say nothing of Jack and myself. Luckily we hadn’t sent both boats through the rapid back to back, as we had talked of earlier. The cost would have been high. (RB)

This sequence of rapids, each of which was a gamble, was later given the name Royal Flush. The first was the Ace; this second one we called Suicide King. Then we continued through the next rapid, the Queen of Hearts, without mishap; if we hadn’t been scared to death, it would have been fun. Shortly thereafter we came to the fourth big one of the day. It was the legendary falls, or salto, that the Mapuche had warned us about, and it deserved legendary status. Briefly described, in this rapid—which came to be known as One-Eyed Jack—the river collides with a boulder as big as the Ritz, splits into two channels, then slices, spits, and erupts 15,000 cubic feet of water per second. We decided to portage.

We unloaded all the gear and lugged it 100 yards down the shore; then we lined the boats through the narrow portions of the river and pushed and shoved them through others. It was difficult to communicate because the roar of the rapid sounded like a rocket at liftoff. In two hours’ time we were back in the boats, tossing on white-capped water as we secured the gear. The lower half of the salto was run easily; the stretch is now called the Ten, to complete the gambler’s hand. A mile downstream we made camp.

After a long, tough, but satisfying, day, we raised a few glasses of pisco and vermouth to the rapids of the Bío-Bío and toasted the looming beauty of the Volcán Callaqui, still dominating our view to the south. Then we dined on spaghetti, soup, and pudding, and lay back for another starry evening with the sound of the river just a few yards from the security of our camp. Our aerial scout and every weary bone in our bodies told us the worst must be behind us.

We pushed off the next day and ran what we thought was a riffle, but it transformed into a Class V rapid (on a difficulty scale of I to VI). George, who was rowing, smacked into every big wave and reversal, and we came within inches of capsizing. Then, without warning, we were in another rapid. This time Jack was swept out of the boat but sprang back in as quickly as he had exited. Next, George repeated the act by being catapulted straight out of the bow. Had we again misjudged the Bío-Bío?

The wildness continued all morning, and despite seven days in the sun, our faces were wan and our knuckles blue. But then the rapids slowly began to ease, and the canyon walls began to taper back. Soon afterward the mountains began to recede and flatten. The first hour of our freedom from uncertainties of the Bío-Bío’s gorge was rich recompense for all the pain and terror. We were through, and the river now rolled in silent majesty.

Here, below the narrow gorge with its small strip of sky and the whitewater that had demanded all our attention, we had a chance once again to appreciate the Chilean scenery. Volcán Callaqui retreated into the maze of cordillera, the solid around us grew rich from the sediment laid down by the Bio-Bio’s floods, and homesteads once again appeared. The branches of the oaks were filled with the songbirds of the south—the Misto yellow finch, the brightly colored red-breasted starling, and the olive-green Chilean elaenia, the bird whose call resonates over the waters of the Bío-Bío.

At 4:00 P.M. we drifted into Santa Bárbara, where Alejandro, true to his word, was waiting with a pick-up truck. We derigged, loaded up, threw a few hands of Frisbee with the locals who had gathered at the small bridge, then drove into town for a final dinner at the firehouse, letting someone else do the cooking for a change.

After celebrating, we wandered to the town square, where we were surrounded instantly by dozens of children. They giggled and hovered around us, all smiles and good nature. As the first norte-americanos to ever visit their town, we were instant celebrities. They brought out a guitar, and we played American folk songs while they clapped and cheered; then they played and sang in the haunting accents of the loving tongue, and it was our turn to applaud. While the pisco flowed and the Southern Cross made its slow pilgrimage across the sky, the Bío-Bío sang its own soft song nearby, a gentle echo of the thunderous symphony of the Andes that had underscored our sleep for the past eight days.

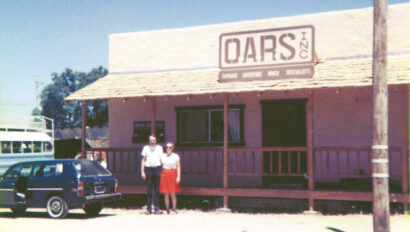

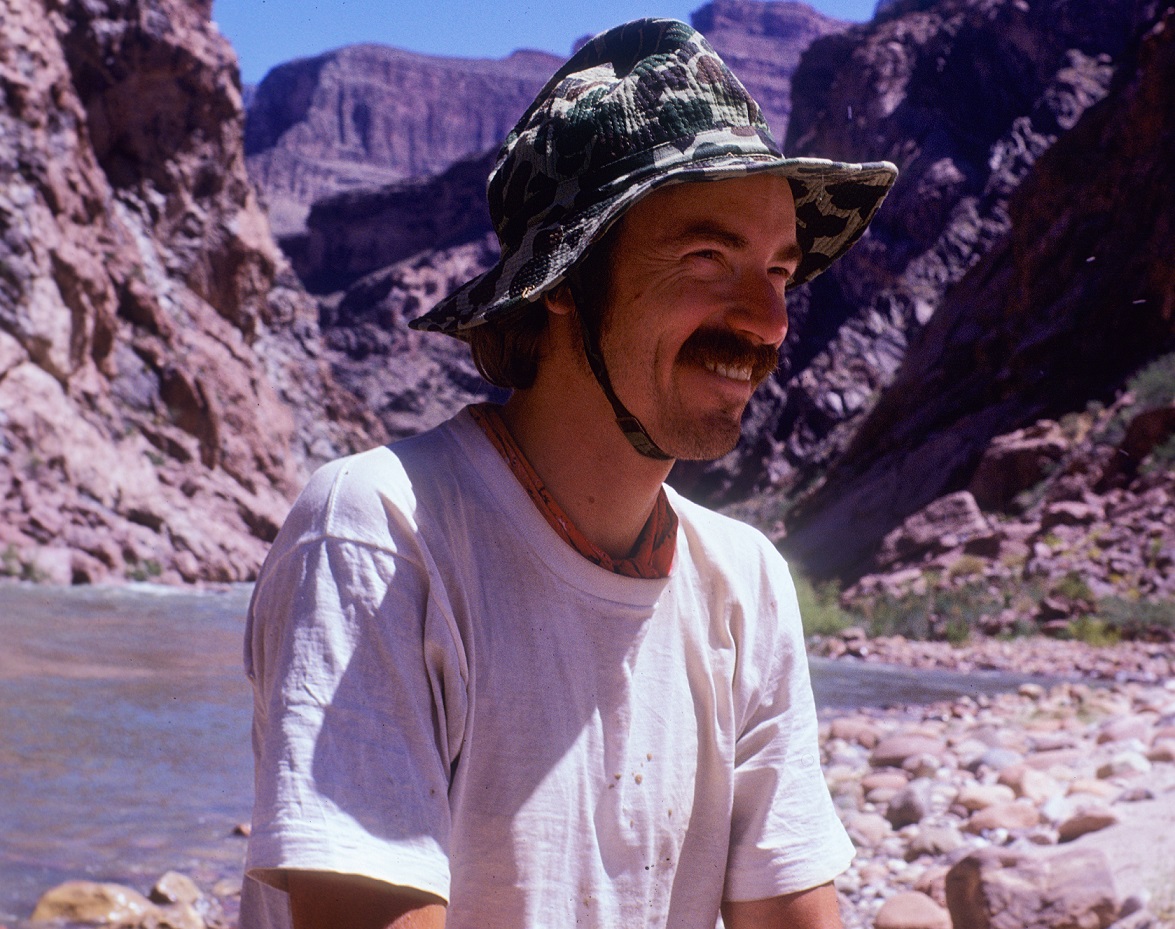

Photos: OARS Founder George Wendt as a young river runner – OARS archive; First descent of Rio Bío-Bío in Chile – George Wendt; Entering Lost Yak Rapid – Jim Slade; Caught in the maelstrom of Lava South – Bart Henderson; Punching the hole in One-Eyed Jack – Skip Horner

Sign up for Our Newsletter