A Game-changer for River Protection: The Loss of the Stanislaus

In June 2016, shortly before his passing, I got the chance to sit down with OARS Founder George Wendt to pry about the early days of running rivers. That day, as we sat in his modest office surrounded by mountains of mementos and articles chronicling his life’s work, we talked about one thing—the Stanislaus—the river that brought OARS to Angels Camp and helped inspire a generation of river advocates.

Where Rafting in the West Got its Start

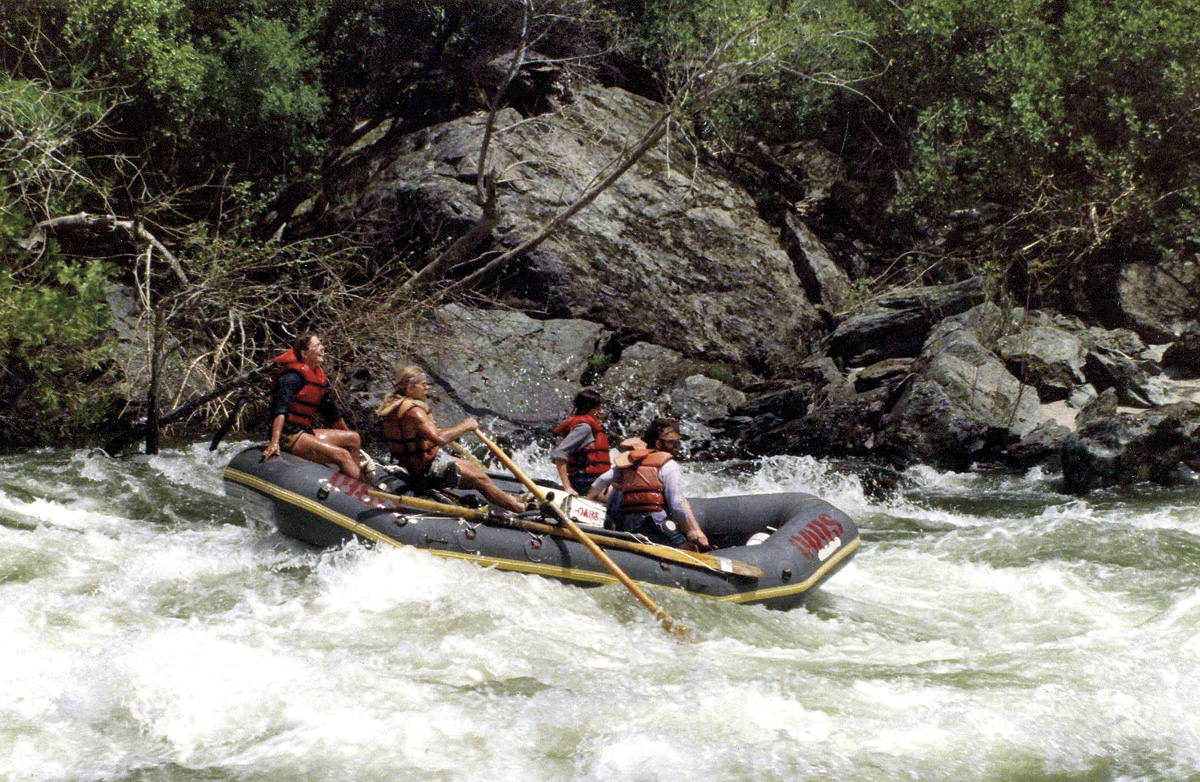

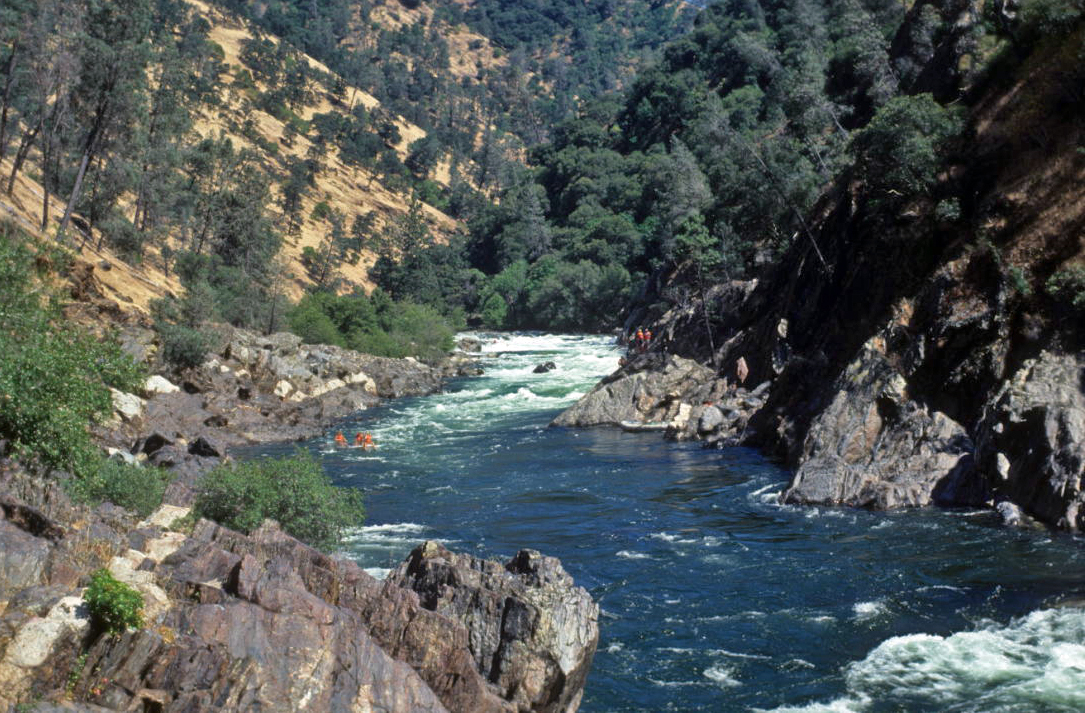

George first came to the Stanislaus in 1967 and by 1969 he was one of 13 outfitters running two-day trips on the weekends. It’s here, in the deepest limestone canyon in California, where the rafting community in the West took off. The nine-mile stretch of river from Camp Nine to Parrot’s Ferry was, by all accounts, the perfect rafting trip, and word quickly spread. By 1974, George and his wife, Pam, decided to leave Los Angeles. Trading his teaching career and Pam’s job as an X-ray technician for outfitting, they moved north to the town of Angels Camp in the Sierra Nevada foothills where OARS could run trips on “the Stan” seven days per week.

According to Tom Huntington, who guided for OARS in the early years and later worked for Friends of the River, the Stanislaus was a true wilderness river canyon. The rafting trip could be done in one day or two (most preferred to do it in two), and had beautiful natural features, including limestone caves you could crawl into, side canyons and creeks, great swimming holes and campsites, as well as relics of Native Americans and the Gold Rush era.

And despite rapids with names like “Death Rock” and “Widowmaker,” the whitewater was fun and straight forward. This was before the era of self-bailing rafts, so it wasn’t very easy to run anything bigger than Class III, according to George. But even more than its accessible whitewater, the Stanislaus was beautiful and gave many people their first taste of rafting.

Save the Stan

Even as some 30 outfitters set up shop and people flocked by the thousands to this famed stretch of whitewater—60,000 people would raft it in 1980—the river was under threat. It was still the era of big dam building and the Army Corp of Engineers had plans that dated back to 1946 to build a 600-foot dam—one of the tallest in the nation—that would flood the Stanislaus under a massive reservoir.

“The year we moved up here in 1974, the dam was already pretty far along in its planning,” according to George in an interview that appeared in Boatman’s Quarterly, Winter 2015/2016. “It was a boondoggle passed by congressional people who’d been entrenched in Congress for twenty years.”

“This was a federally-authorized project for water storage, hydroelectric generation and recreational benefits,” said George. “It sounded pretty good on paper for anybody who had not seen what was going to be lost.”

Regardless of the fact that the New Melones Dam project was well underway, river outfitters and environmentalists believed that very few people actually wanted another dam on the Stanislaus River, so they teamed up to try to block the project from moving forward any further. An environmental campaign, “Save the Stan,” was born and with that, Friends of the River.

The Good Fight

Initially, in a move to stop the project completely, dam opponents worked to get a proposition onto the 1974 ballot—Proposition 17. But according to George, “It didn’t take much to buy the election.”

Big money, supported by California’s agricultural lobby, had launched a massive pro-dam publicity campaign that confused millions of people, especially in Southern California, into voting to dam the river.

“The campaign came out, ‘Save the Stanislaus River, vote no on proposition 17,’” recalled George. “So it was just a matter of confusing the electorate.”

Voting “no” was actually a vote in support of the dam. Using dishonest campaigning tactics, that would later become illegal in California, New Melones dam proponents won by a slim margin.

However, the fight continued. For the next several years, Friends of the River—along with many river outfitters—would continue to raise awareness about the Stan and implement a variety of strategies that would later become the backbone for many large-scale environmental campaigns, including the effort to protect the Tuolumne River as Wild & Scenic several years later, according to Huntington.

“We did everything from statewide initiatives, congressional legislation, state legislation, publicity campaigns, lawsuits, executive orders,” he said. “None of it worked, but it helped us build a constituency that once the Stanislaus was lost, we would be able to transfer—the membership, energy, organization and expertise—right into the Tuolumne Wild & Scenic campaign.”

“I would say that OARS played a key role in this,” said Huntington. “It was part of the ethos of OARS to work to spread the word on environmental values of protected rivers in the West.”

George recalled that the company’s involvement with “Save-the-Stan” was two-fold. At the time, Friends of the River was a fledgling grassroots organization, so OARS, along with many other outfitters on the river, agreed to ask passengers to volunteer an additional $5 per river trip, which would be used to help support Friends of the River’s conservation efforts. He also remembered sending out a tremendous number of two-panel brochures that described what was at stake.

Huntington also remembers OARS taking important stakeholders down the river at no cost, as well as river guides facilitating Friends of the River talks and letter-writing campaigns on every trip.

“‘Friends of the River Talks’ on the Stanislaus became part of river trips…the guides were inspired,” said Huntington. “The guides would stop at lunch and say, ‘For those who would like to hear about the state of this river and its future, please step over here and we’ll talk to you about the campaign to make the Stanislaus a protected river.”

In spite of all of this, the dam was completed in 1978 and would slowly begin to fill. By 1979, there would be one last-ditch effort by Friends of the River’s leader, Mark Dubois, to prevent the reservoir from being filled completely and to preserve the scenic canyon and California’s premiere stretch of whitewater.

“Well past the eleventh hour, in late May of 1979, after the dam was completed and the reservoir rising, Mark would chain himself to a rock at level 808, hidden from view up a tributary canyon. If the water continued to rise, it would kill him.

This would be no stunt. Dubois was willing to die if he could delay filling the reservoir all the way to Camp Nine—where we had started our trip—long enough for America to come to its senses.

As the reservoir would rise toward the expansion bolt chaining Dubois to a multi-ton boulder (Mark would possess the key to unlock the chain around his ankle), California’s Governor Jerry Brown would tell a press conference the Stanislaus was a ‘priceless asset to the people of California and the people of this nation.’ Brown also would ask Secretary of the Interior Cecel Andrus to declare the Stanislaus a Federal Wild & Scenic River.” (Ghiglieri, Boatman, Chapter 1)

After 10 days, Dubois ended his protest and many organizations would also call for the protection of the Stanislaus. Still, the ultimate decision was left to Congress, which in 1980 voted to delete the Stan from the proposed Wild & Scenic list. The fight was over.

By 1982, a series of El Niño storms sealed the fate of the Stanislaus and the beloved stretch of river for so many was gone, buried beneath New Melones Reservoir.

“It was mentally traumatic,” recalled George. “The other big loss I had in my life up to that point was the loss of Glen Canyon. That showed me that beautiful places have to be shared or there’s no constituency that can be mobilized to fight for them.”

The Great Sacrifice

For George, the loss of the Stanislaus became the galvanizing force to help protect the nearby Tuolumne River, which was being considered for a series of three potential hydroelectric dams. But he wasn’t alone.

The sacrifice of the Stanislaus River canyon had inspired a community of activists and forced the country to look at whether or not the still-young Wild & Scenic River System could live up to its intention, according to John Amodio, who was Director of the Tuolumne River Trust at the time.

“We knew that this would be the next battleground and out of the Stanislaus came a much larger understanding from the public about the value of rivers and an informed and engaged constituency,” recalls Amodio. “They grieved the loss of the Stanislaus, but it fortified them with the mentality and commitment of ‘never again.’”

In 1984, 83 miles of the Tuolumne River were designated Wild & Scenic and many more miles of river would follow nationwide in the years to come. The loss of the Stanislaus not only signaled the end of the mega-dam era, but more importantly, it helped inspire the growing environmental movement.

And for George, “never again” would guide his life’s work. He made it his mission to expose as many people as he could to wild rivers so that they would be protected for future generations.

Sources: Boatman by Michael Ghiglieri; Stanislaus: The Struggle for a River by Tim Palmer; California Drought Revives a River — and a Poignant History by Craig Miller, KQED (October 2, 2015) | Photos: OARS. Archives

Related Posts

Sign up for Our Newsletter