True Tales of an Early River Runner

River-running pioneer George Wendt passed away in July 2016 at the age of 74. He wrote this article about his career in 2012.

Glen Canyon: The early days of whitewater rafting

My river journey started in 1962, while I was going to UCLA, when I floated down the Colorado River through Glen Canyon. I found that rafting was a lot easier than backpacking! Right after school was out in June, a group of the Bruin Mountaineers, took off from Hite, UT for a 10-day float through, what I think was, the most magical river canyon in the world.

We had over 20 young people who used a variety of craft, including a canoe, several small rafts, and the Huck Finn-type craft that my friend and I constructed. Our “raft” was made of 12 inner tubes (stacked 2 high), which were lashed together and decked with planking to make a stable platform. I foolishly went on the trip without a life jacket. We maneuvered our raft with canoe paddles although, with a flow of 40,000 CFS in June, we really didn’t have to work to make downstream progress as we floated considerably faster than a hiking speed.

Glen Canyon truly was, as shown in Eliot Porter’s photographs in the Sierra Club’s book, The Place No One Knew, spectacularly beautiful. Eliot’s photos, however, really didn’t do the canyon justice. Glen Canyon had miles of high vertical walls, magical glens and side canyons with countless narrow slot tributaries that were similar to those still available in a few parts of the Southwest like in Buckskin Gulch and the Paria Canyon.

A friend at UC Berkeley shared with me a list of over 20 amazing side canyons to explore that were described in some detail, usually ending with the phrase “normal, run-of-the-mill Glen Canyon spectacular.” Some of the Colorado’s side canyons had a series of giant alcoves that were as deep or deeper than Redwall Cavern. Those of you, who have floated the Grand Canyon, know that it is a long way from the Colorado River’s shore to the back of Redwall Cavern. Now, imagine a tributary of the Colorado River with several such alcoves within a mile of its mouth. One such wonderful side canyon was Twilight Canyon, just downriver from the more well-known Music Temple.

The beautiful hike to Rainbow Natural Bridge was, at the time, about six miles from the river. Less well known were the side canyons of the Escalante River where some tributaries such as Davis Gulch became partially re-exposed in 2005, when the Southwest drought dropped the level of Reservoir Powell, to allow Cathedral in the Desert to re-emerge. You may want to look at the YouTube video: Resurrection: Glen Canyon and a New Vision for the American West, for some ideas about the work conservationists have ahead of them in the fight to drain Lake Powell so that the canyons it submerged can someday be reclaimed.

When the gates of Glen Canyon Dam closed in 1963, the 186-mile canyon above it slowly died over the subsequent years. During that time, my brother and friends and I sea kayaked much of the lower parts of Glen Canyon to hike in the narrow slot canyons that were being flooded. It was the death of this beautiful canyon and its amazing tributaries that galvanized much of my conservation zeal over the subsequent years.

Yampa River: Near-death experience

In 1965, I continued my river journey, by rafting the Yampa River in Dinosaur National Monument. It was there that I narrowly escaped an early death, when a major flash flood created Warm Springs Rapid. We were camped at the mouth of the side canyon right there during a tremendous rain and flood event. The river’s flow, apparently, was temporarily blocked by a huge debris flow that flushed huge boulders into the river, removing about a 100-yard section of the old-growth trees where we had been huddled shortly before. Water backed up above this new river dam, creating a giant mud bathtub ring on both sides of the river upstream, which remained after this new river impediment was breached relatively quickly.

Initially, this new rapid was about the size of Crystal Rapid in the Grand Canyon, but it has been modified over the years. Parenthetically, as some of you may have read, after the rafting season on the Yampa River this past season, there was a major new flood event and/or a major rock fall from the wall opposite Warm Springs Draw which will make running the rapid radically different this next year.

The day after we survived the flash flood and debris flow at Warm Springs, after photographing the new rapid, we floated to our take-out at Echo Park, where the Yampa and Green Rivers join. Then, after an all-night drive to Lees Ferry, I had the good fortune of being able to join a 10-day motorized Sierra Club trip through the Grand Canyon, becoming one of the first 1,100 people to go through the Grand Canyon on the Colorado River. Even though the water was fairly high (running at over 40,000 CFS), and I had only a little rowing experience, I thought that most of the rapids we saw looked like they could be navigated with the 17-foot,10-man military surplus rafts that a couple of friends and I had recently acquired.

Saving the Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon was spectacular! It is hard to believe now, but in 1966 the Bureau of Reclamation was working hard to get approval to build two large dams in the Grand Canyon–one at Marble Canyon and one at Bridge Canyon. These two planned dams would have flooded 133 miles of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. The relatively small Sierra Club, realizing their mistake of accepting the destruction of Glen Canyon, took out full-page ads in the Washington Post and the New York Times: “Should We Also Flood the Sistine Chapel so Tourists Can Get Nearer the Ceiling?” To contact members of Congress in the 1960s, people wrote letters. The Sierra Club ads helped generate a veritable flood of letters, resulting in more mail to Congress on this one issue than on any other contemplated legislation up to that time.

Subsequently, the IRS revoked the Sierra Club’s tax-exempt status. The resulting publicity for the Sierra Club all over the country and the feeling that they were being unfairly targeted led to a quadrupling of their membership in the ensuing months. This fight to save the Grand Canyon further shaped my life. I became an advocate of the position that if the public doesn’t know about how valuable something is, they won’t work to save it. Beginning in 1967, while still living in Los Angeles and working as a school teacher, I worked to begin offering yearly river trips in the Grand Canyon to share the canyon with other people.

The ongoing battle to protect our rivers

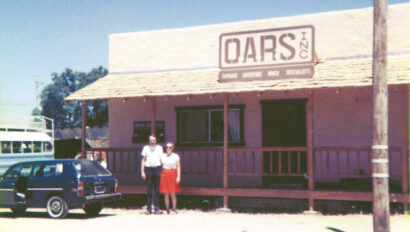

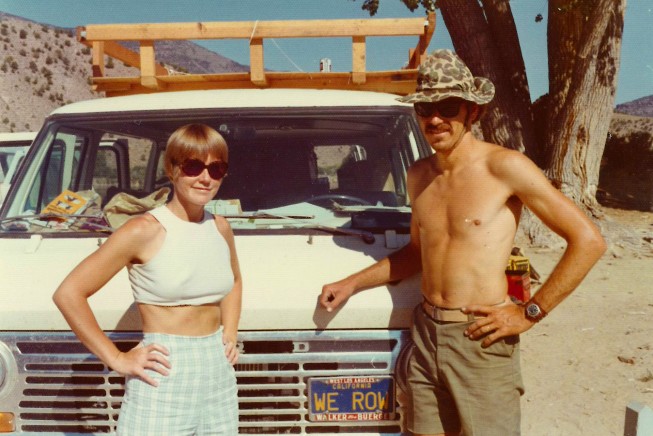

About 1969, I also started running weekend trips on the Stanislaus River. With the ’59 Ford that I borrowed from my brother, it usually took us until after midnight to get to Camp Nine after work on Friday. Then, in 1971, San Fernando Valley had a fairly large earthquake that rated 6.6 on the Richter scale. It rattled the entire Los Angeles area and my wife, Pam, was frightened enough that she wanted to get out of Southern California. She wanted to move back to Minnesota. Since I was a California native, I wasn’t terribly interested in moving to Minnesota. So we compromised on Angels Camp, CA. We moved there in 1974 and raised our two sons, Clavey and Tyler, who I am proud to say, are now working for OARS and putting their energy into making sure that we run good trips.

Living in the Foothills of the Sierra did allow us to run more trips on the Stanislaus River and we soon were offering 2-day trips starting 7 days a week, April through October. We were one of the original 13 companies on the Stanislaus River that worked collectively to negotiate things such as designated campsites along the river and launch times that were designed to avoid having companies in sight of each other while floating down the river. We incorporated a co-op named Stanislaus River Recreation Association, which charged dues so that our new entity could buy a small truck and hire a ranger and an assistant who patrolled the river instead of the BLM.

Back in 1973, a 2-day river trip cost about $45 per person, and the outfitters all agreed to ask their passengers to voluntarily raise the amount they paid by $5 per person (a contribution of over an additional 10 percent of the trip’s cost) to help fund an effort to save the Stanislaus River. The money our passengers paid went to the organization largely founded through the efforts of Mark Dubois and Friends of the River.

During the November 1974 election, we all worked hard to mobilize support for Proposition 17 to save the Stanislaus River. But unfortunately, some well-funded opposition from Bank of America and Guy Atkinson Construction, among others, led to the defeat of our ballot initiative. This loss galvanized the river community’s efforts, however, and the work of Friends of the River, the Tuolumne River Trust (which the outfitters helped fund by adding a voluntary contribution of $10 – $15 per passenger), as well as other conservation organizations, eventually led to the protection of the Tuolumne River with Federal Wild & Scenic designation.

Years later, after New Melones Reservoir filled to the brim in 1983 and flooded the old Camp Nine Bridge and put-in location, an Angels Camp local came up to me at the Calaveras County Jumping Frog Jubilee. He told me, in retrospect, it was apparent to a lot of county residents that they had killed a good economic engine by flooding the beautiful Stanislaus River, which had brought so many visitors into the area.

Then, he turned to me and gave me some advice that has stuck with me ever since. He said, “George, you Stanislaus River runners made a mistake. You should have set up a local company that would have hired local young people to run the river.” He went on to tell me that more of the locals would have then realized what they were giving up when they voted overwhelming, by a vote of about 80 – 20 in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, to flood the Stanislaus Canyon.

I have just returned from a tourism conference which celebrated some notable worldwide conservation successes. The opening address resonated with words which have made a lot of sense to me over the years: “We save what we love and we love what we know.” Those words inspire me to want to do more to share access to our river canyons with our young people and, through education, work to inspire them to want to save our wild places for the future.

Related Posts

Sign up for Our Newsletter